Wars, inflation, health, aging, deadlines, death, AI, work woes – the adult life has no shortage of triggers for anxiety. These worries appear to stick around for a long time with sudden spikes that make them worse. Yet, anxiety rarely feels useful – we are not changing the course of history by worrying about it. How can we tone it down without solving world’s hunger?

I’ve tried a variety of tactics and each has its own place. I never miss the chance to include the subject of thinking errors. They are a major source of anxiety and self-fulfilling prophecies. However, today I’d like to share about the Five Whys, a method of using your non-intuitive slow thinking. The whole reason why I wrote my previous long post about intuition was so I can write this one without explaining what’s a slow brain and why intuition can work against us.

What Are the Five Whys?

When faced with a problem, you ask “why?” at least five times, using the answer from the previous question as the basis for the next. Originally developed by Toyota as a problem-solving tool in manufacturing, it seems to work well for self-discovery. It forces us to goo several layers deeper than the shallow obvious reason for a problem. Here’s a current made-up example.

- “I’m worried that the USA import tariffs may trigger a global crisis” – “Why does that bother you?”

- “I’m worried it might affect my job” – “Okay, it may or may not, Why does that bother you?”

- “I’m worried I may lose income” – “This doesn’t sound great but still, why are you worried about it?“

- “Because I may be unable to provide and my family may suffer” – “Family is there for good and bad. Why does a loss of income, even for a longer term, worry you?”

- “Because I tie my self-worth to how others (or family) perceives me”

And we find something deeper than just “Oh no, Trump”. We’ve reached a core fear that’s fueling the anxiety.

The Core Fears

Asking the five whys for fears appears to bring us down to the same one or two true fears and these seem to be similar for most people. For example (absolutely not a complete or scientific list):

- Fear of failure

- Fear of judgment

- Fear of rejection

- Fear of being alone

- Fear of being a burden

The process of tying one or more of these (or a similar core fear) to some uncertainty-inducing current event can make us panic essentially for nothing. No, Trump won’t make your significant other stop loving you, neither can a potential risk coming to life take away your past experiences. Other things can do that, like being mean, or not listening, but not Trump.

Have I recently shared that we should always be kind? The past acts of kindness, for example, cannot be taken away if you get run over by a car, get sick, encounter dangerous people, communists, experience inflation, or a are attacked by a foreign army.

Why it helps

Anxiety thrives in ambiguity.

Bringing light to the true fears can take away some of their power. The news will never stop blasting the horrors of the day and they will always be awful because this is what makes us watch news. But our deepest fears can be nearly constant for decades, like old friends we don’t really like or want. Nothing is ever going to be perfect.

Brene Brown wrote a book called “The Gifts of Imperfection” where she describes the loss of self, direction, purpose, meaning, safety, certainty, and future. She asks us to seek for our internal self-worth. We are worthy and should accept that, should find reasons for it, and should also not undermine it too much. There is always a need to improve but never a need to be perfect, risk-free, or error-free.

I summarized that book in 2019 with the following text:

If you’re a mess and vulnerable, you are not alone. We are all together in this.

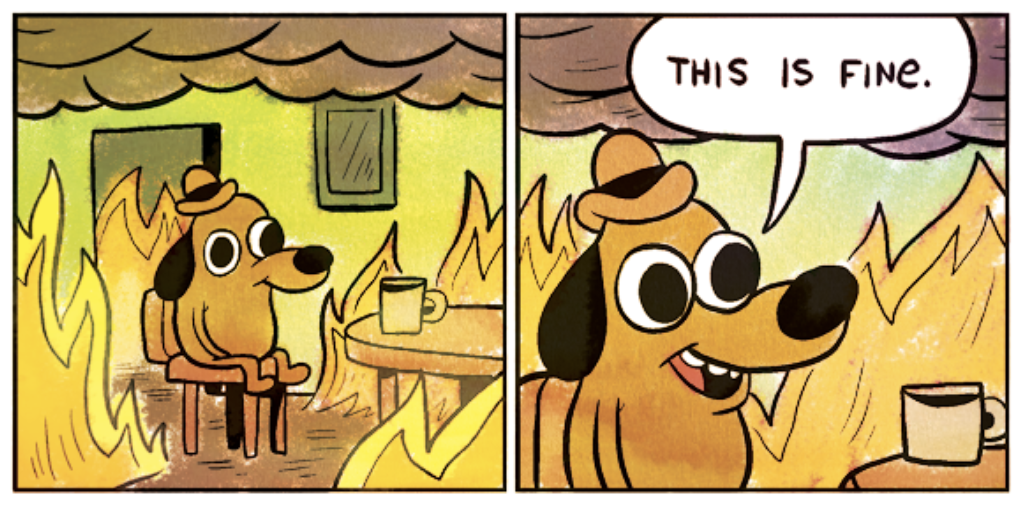

So, to tie it all together, The Five Whys is a method to get anxiety to a point where the level is within Brene Brown’s “This is fine”.